This is an installment of “Sestercenntenial Moments,” marking the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution and its memory in our national life. For more on the background of the series, see here.

Those damned Presbyterians. Always making trouble.

Presbyterianism is one of those splinter Protestant churches that can be difficult to track across time since the Reformation. It took root in the British Isles, especially Scotland, during the seventeenth century as a locus of dissent against the Church of England—which Presbyterians, among others, considered Catholicism Lite, owing more to King Henry VIII’s marital politics and any religious principles. Presbyterians were allied with the Pilgrims and Puritans who came to America and played a key role in the English Civil War. They began coming over in large numbers during the eighteenth century, emigrating from (Northern) Ireland and Scotland in particular.

Which was a problem for the Quakers. The Quakers were an especially radical form of English Protestantism and subjected to persecution for that very reason. William Penn, a warrior turned pacifist, was a Quaker, and was rewarded for his father’s service to King Charles II with the colony of Pennsylvania, a name bestowed by that monarch. Pennsylvania was founded on what might be called principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion, which led lots of people—Europeans, Indigenous people, Benjamin Franklin—to move there. Over time, the Quakers lost control over the colonies to people like the Presbyterians, people with a long history of militancy, theological and otherwise. There went the colonial neighborhood.

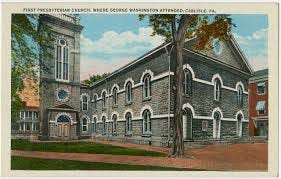

On July 12, 1774, the First Presbyterian Church of Carlisle, Pennsylvania—this was the wild west frontier at the time—hosted a meeting in which attendees declared their independence from Great Britain. My guess is that not everyone there was a Presbyterian, or that all Presbyterians in town agreed with this stance (though the sect was sometimes called “the Fighting Presbyterians” by Loyalists.) The resolution was probably regarded with incredulity, if not outrage, by many in the environs of Carlisle, and in Pennsylvania—far less radical than New England and the Southern colonies—as a whole. Indeed, Pennsylvania, the keystone colony as a function of its size and literally central location on the Atlantic seaboard, would be the locus of the struggle for hearts and minds over the course of the next two years. Twenty years later, George Washington would bring an army into Carlisle to put down the Whiskey Rebellion, whose residents had lost none of their rebelliousness. What was it with those people?

Diversity can be a great thing. But it can lead you to be elbowed aside, and you can lose control of the policies you promote, with unpredictable consequences, which is one reason why it provokes such opposition now. The case of the Presbyterians, who now seem bland to the point of invisibility, also illustrates how identities that matter a whole lot at some moments can be difficult to discern, much less understand, in others.

And that’s the way it seems.