This is an installment of “Sestercenntenial Moments,” marking the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution and its memory in our national life. For more on the background of the series, see here.

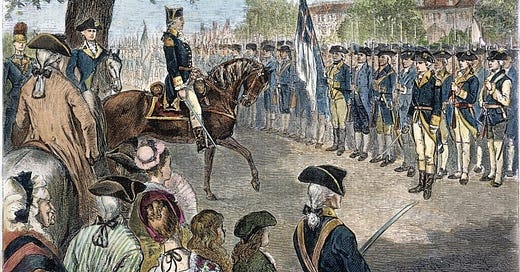

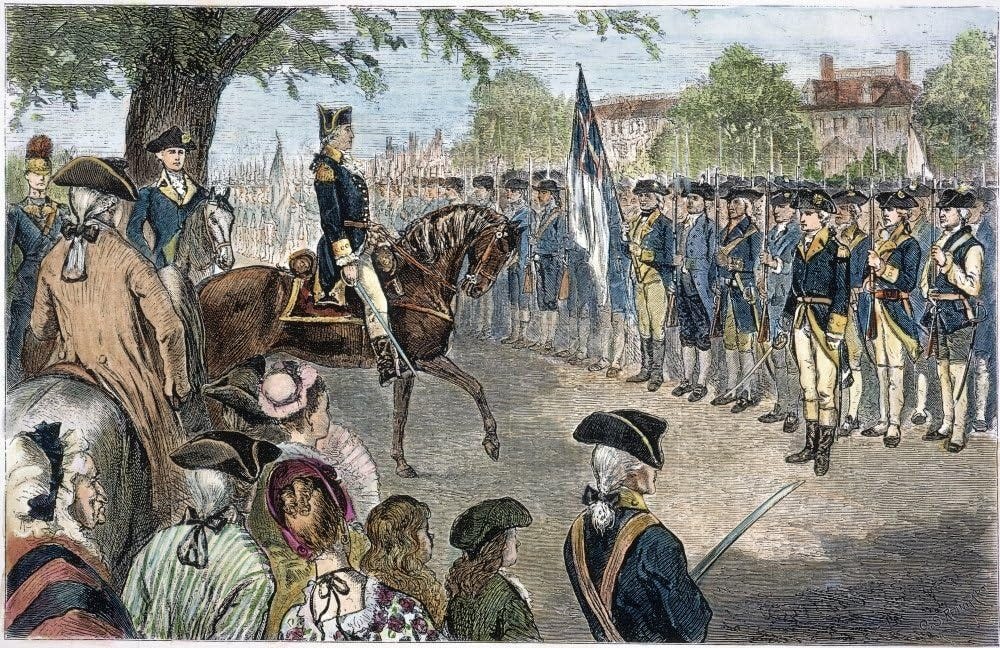

It was a busy Fourth of July—a year before the Fourth of July. On July 3, 1775, George Washington arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to take command of a force that was somewhat optimistically dubbed the Continental Army. That’s for two reasons. First, this “continental” force consisted largely of New England soldiers. And second, they were less an “army” than a collection of militias from the various towns of Massachusetts, farmers—the so-called “Minutemen”—who left the plow to at a moment’s notice to wage battles at Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill that spring, and who now had now pinned the highly professional British army inside Boston. They had accomplished great things. But to accomplish more, they had to be organized into a more cohesive body of men who would sign on to fight longer, and go farther, than most of them ever had.

Washington was the obvious choice for the job to lead them. Almost alone among the Founding Fathers, he had bona fide military experience in the French and Indian War about a decade and a half earlier, where he had demonstrated real courage and leadership experience—the lack of recognition of which from the regular British army had led him to resign. It was Bostonian John Adams at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia who shrewdly nominated the Virginian of Mount Vernon for the post of commander in recognition of Washington’s experience, but also for the symbolic statement of having a southerner lead what was, for the moment, still a New England force. In the months to come, Congress would raise funds, buy equipment, and recruit troops from the thirteen colonies. They did so with borrowed money—and time.

Washington, who refused a salary, left Philadelphia in mid-June and arrived on Cambridge Common—it’s still an open field on the edge of Harvard Square—on this July day. He put on a brave face. “The course of human affairs forbids an expectation that troops formed under such circumstances should at once possess the order, regularity, and discipline of veterans,” he noted euphemistically. "Whatever deficiencies there may be, will, I doubt not, soon be made up by the activity and zeal of the officers, and the docility and obedience of the men.”

Privately, Washington was appalled by what he found in Cambridge. It’s not simply that this was literally a ragged crew with no real experience of military discipline. It’s also that he was dismayed by the character of these men, whose lack of “docility and obedience” was a product of a culture of questioning authority that went back to the origins of the colony a century earlier. There was also the problem that some of them were black—a disconcerting experience for a man who supervised hundreds of enslaved people back home and wasn’t used to dealing with them on a decidedly different basis. These would remain issues for Washington for years, and ones in which he had to—and did—adapt. This is one of the sources of his greatness (and a reason, amid strong resistance from his family, why he ultimately emancipated his slaves). For the remainder of the war, Washington had to grapple with the reality of a Continental Army that was never paid, fed, equipped, or trained as much as he might like, along with another one that he would in fact need local militias to achieve his objectives. Washington’s finest hour as a commander, both as a matter of personal bravery and spontaneous leadership, took place at the Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey in 1778, in which the role of local state militia was crucial.

Meanwhile, back in Philadelphia in that early July of 1775, the members of Congress were trying to find a different kind of balance. Radicals like Adams and Thomas Jefferson were eager to ratify a break with Great Britain that reflected the fact that shots had been fired and that Massachusetts was already running an independent government. But there were plenty of representatives of states—among them John Dickinson and Joseph Galloway of the keystone colony of Pennsylvania—who were still looking for an off-ramp for a continent-wide war. To exhaust this increasingly unlikely possibility, Dickinson drafted the Olive Branch Petition (a document that Benjamin Franklin had a hand in editing). Because the colonists had been engaged in a dozen years of struggle with the British Parliament, this was a Hail-Mary pass to go over its head and appeal directly to King George III, with whom there had actually been a real history of mutual goodwill. The Olive Branch Petition was ratified on July 5, 1775. But by this point, the British monarch had lost patience with these subjects. He roundly rejected their gambit in August, news which reached Congress in September. By summer’s end, the point of no return had truly been reached.

So it was time to actually declare independence. Well, not exactly. There were more important things to do: an economy to create, treaties to negotiate, battles to fight. It wouldn’t be until the next summer that Jefferson—very much a junior member of the Virginia delegation—was delegated to write the press release that sealed the deal. But that wouldn’t happen until the next July.