The late great comedian Andy Kaufman had a routine in his child-like mode—Kaufman was a man of many personae—where he began singing a familiar drinking song to his audience: A hundred bottles of beer on the wall / A hundred bottles of beer / Take one down, pass it around / 99 bottles of beer on the wall. The audience chuckled as he made his way down the nineties, their amusement tapering as he got into the eighties. Soon the crowd was bored, then restless, and then angry. Still Kaufman sang on until he reached about ten bottles of beer—and then stopped. Now the audience was furious for a different reason: having gone this far, it was desperate for him to finish. After prolonging the agony, Kaufman resumed. By the time he got to zero, everyone was cheering with cathartic release. And then Kaufman sang, A thousand bottles of beer on the wall ….

I was reminded of this comic masterpiece as I made my way through Ron Chernow’s new thousand-page biography of Mark Twain.

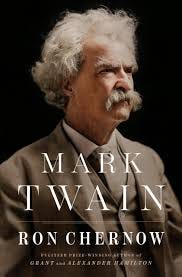

It’s become my custom to take on a really big book each summer. In recent years, I’ve focused on classics of English literature: Daniel DeFoe’s Moll Flanders (1722), Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield (1850, along with Barbara Kingsolver’s delightful 2022 reimagining in Demon Copperhead) and Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones (1749, made into a really fine 1963 movie that won the Best Picture Oscar). Ron Chernow is one of those people whose books I buy sight unseen after the pleasures of Hamilton (2004), Washington (2010), and Grant (2017). The reviews of this one were less glowing—I read complaints that it went on too long—but I was willing to see for myself. I’d read a couple of Twain bios already, notably Justin Kaplan’s 1966 classic Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain (I was reading it on my wedding day in 1989), but I figured Chernow would be definitive.

The first half of Mark Twain, much of which I read while vacationing over the July 4 weekend, was absorbing. Chernow rendered Twain’s life and sense of humor vividly; I laughed aloud repeatedly. By about page 400, I’d reached the writing and reception of his 1890 novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, which I long considered his last major work. But I still had over 600 pages to go.

I didn’t mind for a couple of hundred more. Chernow is particularly good at explaining Twain’s career as a businessman, which I never fully appreciated. More specifically, I hadn’t realized the full range and intensity of his enterprises, in which he made—and lost—many millions of dollars in a failed effort to become the Oprah Winfrey of the 19th century. He had friends in high places who saved him from utter ruin, and Twain (along with Walt Whitman) was an early exemplar of a celebrity culture that gave him cultural currency until the very end of his life. Indeed, he was probably more famous as a live stage performer who mounted a series of global lecture tours than he was a novelist. And yet his genius as a writer was recognized in his lifetime, and notwithstanding woke efforts to muzzle him in the 21st century—I’m not sure it was cowardice or discretion that led me to stop teaching The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at Fieldston—he remains a potent force to this day, as indicated by Percival Everett’s racially rewired novel James, which won the Pulitzer Prize this year. (I thought it was OK, better in its first half than its second).

By about page 700 of Mark Twain, I felt a little bit like a member of Andy Kaufman’s audience: I was too far in to walk away, but increasingly exasperated the further I got. Chernow goes into numbing details of Twain’s marriage, his (truly tragic) relationship with his children, and his various travels in Europe and America. I began to find Twain increasingly tiresome, and his family and business associates began to seem like unwelcome houseguests who took up too much space in the book. I don’t think Chernow was trying to write a revisionist biography—though clear-eyed, he tends to admire his subjects. But I feel like Twain really came out of this one tarnished in my eyes. I’m not sure Chernow is doing anybody a favor here.

He seems to make two elemental mistakes. The first is in thinking that just because he has lots of source material—which of course is his specialty as a researcher—that he has to use it. The other is in failing to recognize that, however important or colorful Twain’s life was, his final decade or so was simply less interesting than that of Hamilton or Washington, whose careers were still quite active until the very end of their lives. Chernow’s editor is the highly esteemed Ann Godoff of Penguin. My guess is that she would have seen this problem, but, well, Chernow is Chernow—a kind of modern Mark Twain of biographers. Twain was similarly a victim of his own success in his later work, especially after he lost his wife, Olivia, who was probably his most important editor.

It was in considering this that I remembered Titan, Chernow’s 1998 biography of John D. Rockefeller. I took on that similarly massive tome one summer some years ago, and gave up about halfway through—something I rarely do. But probably should do more.

Relieved to finally finish Mark Twain, I’ve pivoted, a little belatedly, to Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance, currently inhabiting the New York Times bestseller list, a few notches below Chernow. It is, not surprisingly, exceptionally well-written. And, at just over 200 pages, blessedly short. Sometimes, less really is more.