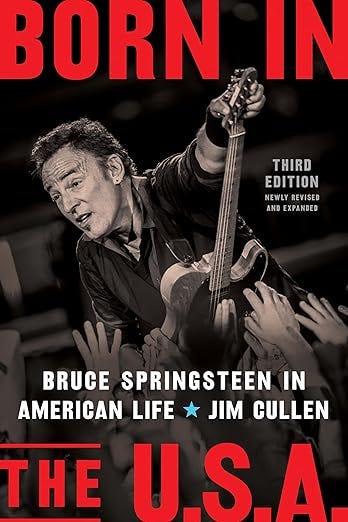

The following is an excerpt from the revised and updated third edition of my 1997 book Born in the U.S.A. published today. Here I write about my decision to return to the subject after an interregnum of many years. I hope you find it entertaining. —Jim

In the drama of our individual lives, we each have a large cast of supporting players. Some are with us over the course of many decades. With others, our dialogue may be relatively brief but intense. Still others periodically wander on or off our stages, characters we find amusing, bemusing, or irritating when we encounter them in short scenes of lesser or greater personal significance. Such are the means by which our stories are scripted.

There’s another set of people in our lives worth noting here: people we’ve never met with whom we may nevertheless have a meaningful relationship. Some of these figures are long since dead—ancestors, literal or figurative, whose legacies affect the way we live in the present. Others may come into our lives more indirectly, like distant bosses for whom we work or celebrities who happen to be our generational peers. We may not be able to address such people directly, but we are nevertheless engaged with them in ways that are no less meaningful, even if it happens to be silently.

For tens of millions of Americans, Bruce Springsteen is one of those people. We began listening to him at different points and different walks in our lives, with greater or lesser degrees of intensity. For many of us, this relationship has been lifelong. One reason it’s often been intense is that Springsteen himself has shown a high degree of consciousness about his audience, as revealed in things he’s said and choices he’s made, in a career that’s now spanned more than a half-century. The fact that you’re reading these words is evidence of that bond—and evidence of a longing to be part of a larger community. In an important sense, it is that community—one that extends back long before any of us were born, and which will live on long after we are gone—that’s the main reason for this book: to stake our place in a grand saga. I’d like to take a moment why and how I tried to write it, in the hope we can understand our time, our place, and our roles in that saga a little better.

I think of myself as a second-generation Springsteen fan. The first generation—people I’ve read about and listened to for many years—witnessed the immaculate conception of the Springsteen legend. They were there on the Jersey Shore, in the clubs, and at record stores for Greetings from Asbury Park and The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle. The first apostles who evangelized for Springsteen—those right there in Asbury Park, like Robert Santelli, followed by the national rock critics of the 1970s whose careers coincided with a golden age of music journalism—were people who rubbed elbows backstage with him, relating what they heard from first-hand experience and direct conversation. There was nevertheless a sense of awe about their encounters, reflected as early as 1973, when Peter Knobler and Greg Mitchell for the early rock magazine Crawdadddy, wrote “Who Is Bruce Springsteen, and Why Are We Saying All These Wonderful Things About Him?” The “rock critic establishment,” a term coined by Village Voice writer Robert Christgau, consisted of figures like Lester Bangs, Jon Landau, and (a little later) Dave Marsh, all of whom lionized the young Springsteen. (Landau became his producer and manager; Marsh his biographer).

I was a child when all this happened. I had older, savvy, cousins, and that’s how I saw the covers of albums like Born to Run and Darkness on the Edge of Town as an early adolescent, but they didn’t mean much to me. It was only with the release of The River in 1980, and Springsteen’s first hit single, “Hungry Heart,” that I snapped to attention. And haven’t stopped listening since.

I was an ordinary specimen in the Springsteen demographic: young, white, suburban (and, I used to think, male, but I’ve come to learn that Springsteen’s female audience is also considerable). Also, like many such people, I was upwardly mobile—and inclined to romanticize the working-class roots I was leaving behind. Born at the tail end of the Baby Boom, I was late to the party in any number of ways, among them for Springsteenmania. A student journalist with inchoate literary ambitions, I lacked the experience, imagination, and worldliness of that first generation of Springsteen enthusiasts. But I was nevertheless sufficiently obsessed to spend my senior year of college writing a thesis on Springsteen. I look back with affectionate gratitude for my advisor, the distinguished ethnomusicologist Jeff Todd Titon, who patiently endured my song-by-song reading of Springsteen’s catalog, an effort more notable for its enthusiasm than insight.

However, I did go on to acquire one thing that the previous generation of Springsteen writers did not: a Ph.D. I completed a doctorate in American Studies with the hope it would teach me how to write books. And so I did, beginning with a dissertation on how the Civil War has been portrayed in 20th-century popular culture, and a second book tracing the rise of the mass media from the colonial period to the present (which was to say the end of the twentieth century). It was then, while holding a junior teaching post at Harvard, that I circled back to my adolescent obsession and began work on the first iteration of this book.

It was clear from the outset what it could not be: an insider or biographical account of Springsteen’s life and work. What I thought I could do is situate him historically in what my editor told me to make the subtitle of the book: “the American Tradition.” I didn’t like the phrase—in an age of multiculturalism I was rightly uneasy about that definite article—but like a lot of ambitious people, I made compromises. I couldn’t be an apostle, but there was still room to be St. Paul: the outsider who codified and spread the Word to Gentiles in the groves of academe.

The fact that Mr. Springsteen had not been crucified, much less resurrected, was only the first in a series of problems with this conceit. Another was my callowness and relative youth, in which I failed to see the degree to which my work would be seen—and in fact was—a “clip” job in which I depended heavily on existing sources that I didn’t always interpret in compelling (or sufficiently well contextualized) ways. If my lack of self-doubt wasn’t exactly a saving grace, it did endow me with enough doggedness to pursue and achieve publication. I distinctly remember a night on an Amtrak train ride commuting between Boston and New York in the winter of 1997, a few months before publication, when I suspended my usual caution about such things and allowed myself to believe I was on the cusp of becoming rich and famous.

An equally vivid memory—the realization this wouldn’t happen—occurred while on tour to support the book, in a hotel room in West Long Branch New Jersey, overlooking the boardwalk that ran through Springsteen’s beloved Asbury Park. My life would take a somewhat ironic turn: within a few years I would leave Harvard to become a high school teacher, but would also burrow into a quarter-century of writing academic books for university presses.

There was a lot of uncertainty amid this struggle to find my level, but one thing remained clear: I was done with Springsteen for the foreseeable future. The idea of successfully staking a claim to such territory seemed not only unlikely but pathetic, and in the years that followed I wrote about a variety of subjects, among them the American Dream, Roman Catholicism, the U.S. presidency, television, film history, and even a foray into fiction. I continued to follow Springsteen’s career, of course, and watched as a steady stream—perhaps more accurately a flood—of books entered the publishing bloodstream, among them works by Springsteen himself. I reviewed a couple, wrote an occasional essay or two, but had no intention of going back in any substantial way.

In 2018, I was approached to write a piece for Long Walk Home, a collection of essays organized to commemorate Springsteen’s 70th birthday the following year. I was honored to be included among a set of authors that included the great rock critic Greil Marcus, novelist Richard Russo, and Peter Ames Carlin, author of a bestselling Springsteen biography, as well as a host of younger scholars who took Springsteen’s work in entirely new directions. Because the editor of that volume, with whom I was eager to work again, specialized in the regional history of the New York metropolitan era, I pitched an idea comparing the careers of two native sons: Billy Joel of Long Island (about whom I had started and dropped a manuscript) and his geographic reverse image in Bruce Springsteen of New Jersey. The project, Bridge and Tunnel Boys, was published late last year.

Having now re-immersed myself in Springsteen land, I decided I wanted to return to this book. And, finally, just possibly, to get it right—or, at any rate, make it a little better as I explored Springsteen’s relationship with republicanism, democracy, the American Dream, the work ethic, masculinity, and religion. That’s how you and I ended up here together on this screen. Perhaps we can meet again on good old-fashioned paper.