Diary of the Late Republic, #21

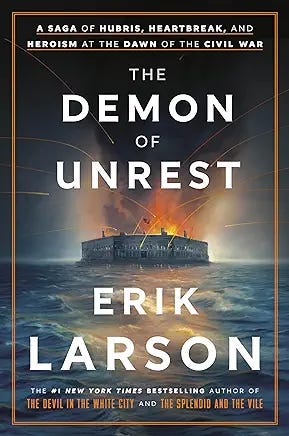

Erik Larson’s history books are like your favorite mystery writer: you pretty much know what you’re getting, which is exactly why you pick them up. (Pretty much: you want familiar, but with a twist. That’s how pop culture works.) Larson’s masterpiece remains Devil in the White City (2003), a truly haunting gothic story from the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893, but his last book, The Splendid and the Vile (2020), about Winston Churchill in Britain’s finest hour, is among his best. His new one, The Demon of Unrest is about the fall of Fort Sumter and the outbreak of the Civil War. I’m about halfway through. It’s fine—not great, but pleasant enough.

What I’ve really been thinking about as I read the book, though, is the review that ran in the New York Times Book Review a couple weeks ago by Alexis Coe, a habitué of elite media and author of the cheekily titled 2020 debut You Never Forget Your First: A Biography of George Washington (which I just ordered). Coe really doesn’t like The Demon of Unrest, which she explains in a review with the headline, “Maybe Erik Larson Should Have Left the Civil War Alone,” one she surely didn’t write, but accurately reflects the spirit of her review. Here’s one key critique:

There was something lacking in the book’s 565 pages: Nary a Black person, free or enslaved, is presented as more than a fleeting, one-dimensional figure. Frederick Douglass, a leading abolitionist and standard of histories of the era, warrants no more than a mention.

Black people are primarily nameless victims of an antagonistic labor system that’s causing a political crisis among white Americans. At one point, to differentiate this near monolith, Larson employs the term “escape-minded Blacks,” a curious turn of phrase that suggests there were “bondage-minded Blacks.”

There’s some merit in this critique. But strikes me as heavy-handed. Like it or not, this particular military and political precinct of the American War is not typically one where questions of emancipation are foregrounded. As Coe notes, Frederick Douglass was not exactly lacking attention at the time, and you’d be hard-pressed to avoid him in high school or college English departments now. And, in fact, there may well have been blacks who, for one reason or another—health, loved ones, timing—may not have been “escape-minded” in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1861 for any number of reasons, as much as modern sensibilities may want to insist they had to have been. You’d really have to bend Larson beyond recognition to suggest that he was in any way sympathetic to slavery, and the book in fact is attentive to its human cost, even if he doesn’t foreground human agency.

But that’s not really the point that sticks with me. Instead, it’s Coe’s dismissive, condescending description of Larson as “the reigning king of Dad History.” Don’t get me wrong: in publishing terms, he’s an 800-pound gorilla who hardly needs defending from the likes of me. Actually, “Dad History” really clarifies some things. Like “Dad Rock,” it’s implicitly conservative, maybe even a little bit musty. But it’s indicative of a kind of mental comfort food that gets maligned too quickly. To be sure, it should be part of a balanced historiographic diet. But I think there’s a little too much of what might be called History Health Food, which typically involves telling us why all the things we love are bad for us and the planet, and why we should instead be thinking more critically about our bodies of knowledge.

I’ve spent a lot of my career trying not to write Dad History. Now I would regard it as a real accomplishment.

Oh, and by the way: by my count, six people have asked me about the book while I was reading it, noting they were Larson fans. Four of them were women.