Great is Liberty! great is Equality! I am their follower;

Helmsmen of nations, choose your craft!

where you sail, I sail, I weather it out with you, or sink with you.

—Walt Whitman, “Great Are the Myths”

Diary of the Late Republic, #25

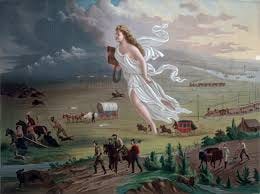

I was happy to see recently that Richard Slotkin, last of the classic American Studies scholars, is out with a new book at the tender age of 81 (he was trained by my mentor, the great Jack Thomas of Brown University). Slotkin’s first book, Regeneration Through Violence (1973), was the first installment of a trilogy that included The Fatal Environment (1985) and Gunfighter Nation (1992). Slotkin is a product of the mid-twentieth century “Myth and Symbol” school of American Studies, which began as an effort to understand what made the United States exceptional—and exceptionally resistant to totalitarian ideologies like Nazism and Stalinism. Slotkin turned this affirmative impulse on its head to instead argue that the governing myth of American history—the frontier—was a uniquely destructive metanarrative rooted in a bonanza theory of economic development, ruthless conquest, and a belief in the necessity of bloodshed as a purifying ritual by which national ambition and energy could be sustained. Few scholars today would embrace his old-fashioned approach of textual reading (American Studies has long since balkanized into a series of particularistic subdisciplines rendered in theoretical language), but Slotkin was describing what we now call settler colonialism long before it was fashionable.

Slotkin’s new book, A Great Disorder: National Myth and the Battle for America, recapitulates his frontier thesis but augments it with a series of additional ones that have grown up alongside it in the last two centuries. Such myths—defined here as the prevailing common sense for a group of people that cannot be empirically proved or disproved—function as origin stories that are used to explain the present and justify a future course of conduct. So it is, for example, that we have the Myth of the Founding, by which the birth of the United States alternately becomes a precedent for action or the demarcation point of limits beyond which we should not go. The Civil War, he says, spawned three competing myths: one emphasizing the broadly emancipatory power of abolition, a second valorizing the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, and a third a romance of reunion by which bygones (and the interests of black people) were largely forgotten. The twentieth century saw the emergence of more reformist narratives: the Myth of the Good War, centered on World War II, and the Myth of the Movement, centered on the Civil Rights struggle. Both of these have been routinely invoked in the decades since as a usable past that furnishes a basis of hope and direction for any number of progressive causes.

Reviewers have complained that Slotkin’s analysis gets fragmented and hard to follow as he approaches the present, and I do think he loses the forest through the trees in what becomes a largely partisan analysis of the last 20 years. But it’s useful to think about the fossil fuel industries as frontier cultures, for example, and to understand the quest for the Affordable Care Act (and the Obama presidency generally) as a continuation of the Myth of the Movement. In any case, he’s surely right that we need collective stories that give us a sense of hope and purpose, and his critique of the contemporary left as leaning too hard on deconstruction than reconstruction rings true.

Since finishing the book I’ve tried to imagine other myths that have sustained us in the past 400 years. I of course have spent a long time thinking about the American Dream (a myth that Slotkin acknowledges, but is not particularly interested in developing because he says it lacks a single master story; I’m not sure I find that a credible reason to dismiss it). The best alternative/variation I could come up with is what might be termed a Myth of Progress: a belief in improvement as the hallmark of the national experience. In the colonial era, progress was defined in religious terms (particularly in terms of dissidence from the Church of England and the embrace of alternative sects like Quakerism). In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, progress was largely political—the founding, but also the democratization of American society in the Jacksonian era. Then it was economic, grounded in the Industrial Revolution. And for the last century, progress has been understood as egalitarian, whether in terms of economic redistribution or the amelioration of oppressed minority experience.

But we don’t really seem to believe in the past as an inspiration for progress anymore. Those on the right see it as something of a lost cause; those on the left see U.S. history in terms of structural oppressions. Hope—for so long considered a source of the American character, back when we spoke of such things—has largely evaporated. We need to get it back. I wish we could find a way toward our myths as a source of inspiration for brighter futures yet unknown. I wish I had a bigger imagination.