Jersey Bound

A few words about, and from, my new book

Please note: Americana will pause for the next week or so while I’m on Spring Break.

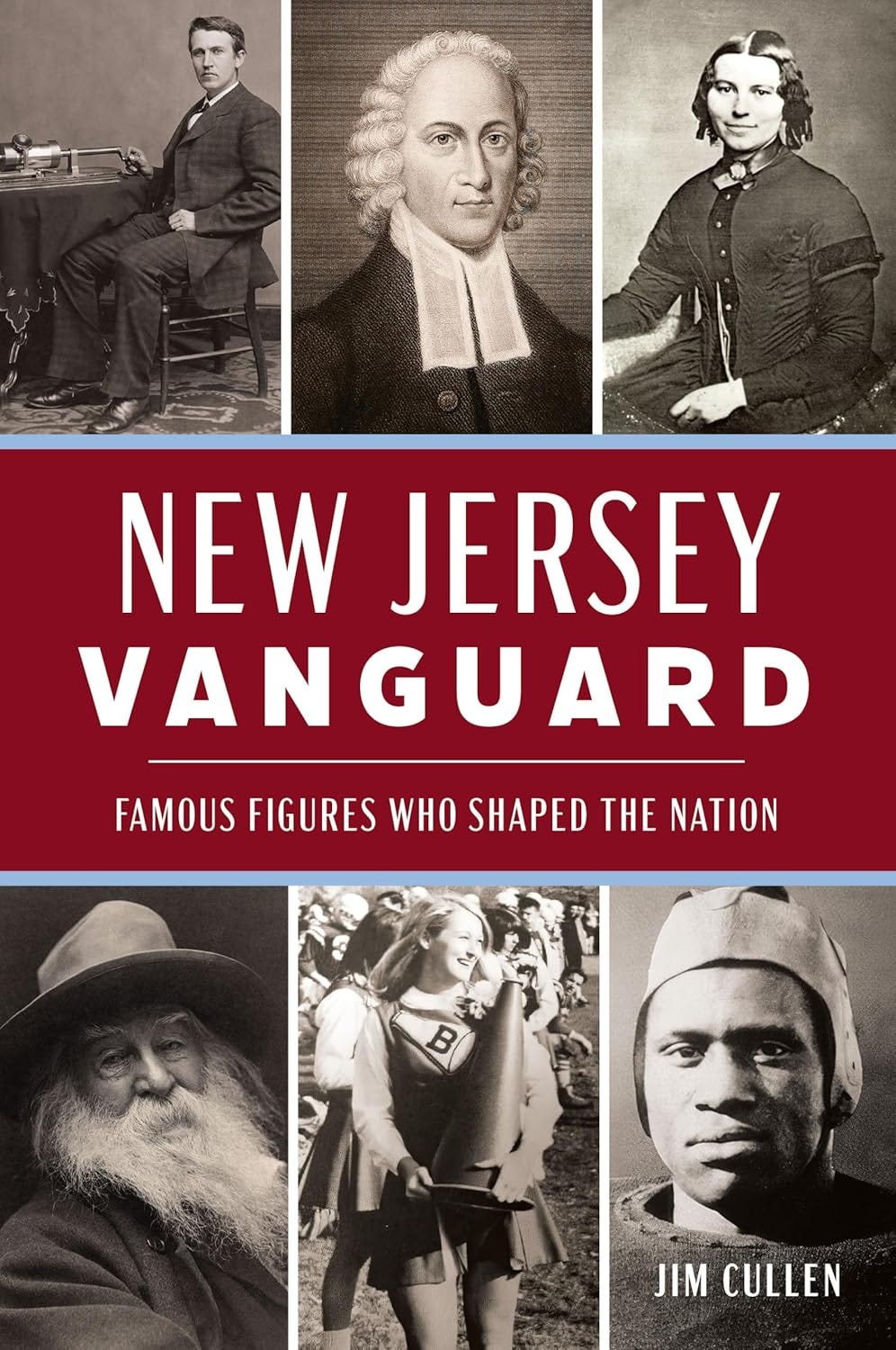

Today is publication day for my latest book, New Jersey Vanguard: Famous Figures Who Shaped the Nation. The slim volume is a set of a dozen biographical portraits of people—some native, some not—who in the last 400 years made a name for themselves nationally in New Jersey. That list includes people like Aaron Burr, Walt Whitman, Thomas Edison, and Meryl Streep. New Jersey Vanguard is a decidedly modest entry in a decidedly modest body of work.

It had a somewhat circuitous process making it into print, which began three years ago when I found myself in conversation with an editor I liked, whose bailiwick was local history. I pitched the idea, which he thought promising. Hoping that the contractual hurdles would be cleared, I drafted two chapters on George Washington and Whitney Houston (now that’s a pair, no?). But then I came up with the idea that became Bridge & Tunnel Boys, my book comparing the careers of Billy Joel and Bruce Springsteen, which of course has a local—that is to say metropolitan New York—angle. I put that project on the front burner (this for me is what counts as “major” work). Upon completing that in the spring of 2023, I picked up this older New Jersey project, only to find my path blocked by the series editor in which my editor hoped to place the book, who found this “white dude” insufficiently DEI. Shortly after that I was solicited by an editor at The History Press, a South Carolina outfit that specializes in local history. I sold the idea to him and finished the book between September of 2023 and March of 2024.

The History Press has a very different model than most publishers I've worked with, in part because they don't focus on Amazon, instead taking a hyperlocal approach to marketing. Which I believe means you'll find this book at CVS, Walgreens as well as Barnes & Noble and other local bookstores in the Garden State—but pretty much only there. Great density, local ambit. I like trying different things while keeping my expectations modest.

Below is an excerpt from the book. Hope you find it worth a look. In the meantime, I continue to work on another local book about which I am more invested—on women in colonial and revolutionary New England. This one is slated for publication in June 2026—just in time for the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution.

Introduction: Middle State

This story, like a great many stories about New Jersey, begins overseas with a place in the middle.

The island of Jersey—officially known as the Bailiwick of Jersey—is located in the English Channel between Great Britain and France (in fact, closer to the latter than the former). Though it is one of the British Isles, Jersey does not belong to the United Kingdom but is rather a self-governing Dependency of the British Crown. Originally part of the French duchy of Normandy, the island has pledged its loyalty to England since the thirteenth century, an identity reflected in language, currency and the fact that cars drive on the left. Jersey was caught between centuries of warfare between England and France and has been occupied a number of times, most recently by the Germans for five years during the Second World War.

During the English Civil Wars of the mid-seventeenth century, Jersey was ruled by George Carteret, who had served as comptroller of the English navy and as an ally of the of the exiled King Charles the II. When Charles ascended to the throne in the Restoration of 1660, his brother (and future King) James, the Duke of York, gave Carteret a tract of land in the American colonies between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. James dubbed it as the colony of New Jersey (more on this, and the complications surrounding it, in chapter 1). And so it is that a middling place on one side of the world became the namesake of middling place on the other.

This middling status is multilayered. New Jersey began its life as part of an English empire sandwiched between two more powerful ones: France to the north and Spain to the south. Even within the English (later British) empire, it occupied a middle zone between relatively homogenous mercantile New England colonies above and the agrarian, racially segmented South below. New Jersey’s middle status goes one step further: it was right smack in the middle of the so-called Middle Colonies, wedged between the much larger New York and Pennsylvania, jostling between the other small middle ones of Delaware and Maryland.

Indeed, New Jersey’s significance can seem to rest on its relative insignificance. The state is smaller than forty-five of the fifty in the Union; its population falls somewhere in the middle of the pack. It occupies a mere sliver of Atlantic coastline. And yet while the state is certainly right smack in the middle of that seaboard, one could hardly call it the heartland of a continental nation that stretches three thousand miles to a different coastline, part of a Pacific rim that is now emerging at the focal point on the globe.

But one can turn also such characterizations of New Jersey inside out and say that the state sits at the very heart of the nation and its history. The mixed economy and demographic diversity that have defined the United States have been hallmarks of New Jersey from its very origins. It also sits at the crossroads of the most important structural shifts in American history: from farm to factory, from country to city, from city to suburb. Slavery to freedom, agriculture to industry, manufacturing to services, services to information—it all happened there. New Jersey is literally a crossroads as well, a node of transportation in terms of shipping, rail, interstates, and fiber-optic cable. It’s not necessarily unique in these regards—but its very typicality, its utter ordinariness, is why it matters. To paraphrase Walt Whitman (the subject of chapter 6), New Jersey is large; it contains multitudes. It is a synecdoche for America.

Like other American places, New Jersey has its native sons and daughters. But it was also a place where a great many Americans found themselves, by accident or choice, at key moments in their lives. It is this alchemy between native and adopted, lifelong and temporary, that gives a place its sense of texture and significance.

And provides the occasion for this book. New Jersey Vanguard is a study that spans four hundred years of history to explore how this Middle State became a crucible for a dozen American lives. Sometimes these are origin stories; sometimes New Jersey is the place where life stories ended. In other cases, it was a crossroads, a place where choices were clarified, decisions were made, courses were changed. In the pages that follow, you will encounter people who dedicated their lives to politics, the arts, religion, scholarship and the military, among other pursuits. Each in their way were paragons of excellence, though all were deeply human. As such, their stories illuminate ours.

And so it is that we begin—in the middle.

Jim, you're an astonishment!

Interested to read about Jersey. Interesting that one of the prison ships anchored in the East River during the Revolutionary War was HMS Jersey. One of 13, I believe, prison ships in Wallabout Bay, now Brooklyn Navy Yard section. It was considered the low point in British Naval history, since its conditions led to the deaths of more than 11,500 colonists, known as the Prison Ship Martyrs. I have plenty on this. the remains of those martyrs lie in slate boxes in a crypt below Ft. Greene Park, between Bed-Sty and Downtown Brooklyn. There used to be a plaque there highlighting the martyrs, but was taken down for refinishing years ago, not sure if it was ever re-installed. the crypt is opened by the Parks Dept. every so many years, but not for the public. But a historian like you should have a shot at access if desired. Few can believe that there is a mass crypt in Brooklyn containing that many heroes' remains. Most were given the choice after capture of joining the British forces, or remaining/dying on the Jersey and other ships. PW