As some of you know, I am slated to become a grandfather in 2025. To mark the occasion, I have begun writing letters to my prospective granddaughter, which I hope will ultimately become part of a larger project that tries to capture what it’s like to be alive in the first quarter of the twenty-first century. I hope it will be of some value to you now and her later. —Jim

Dear Baby,

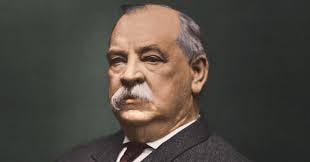

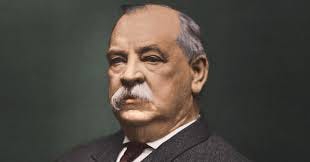

Today is inauguration day, which means that a man named Donald J. Trump will officially return to the presidency after a four-year break. (There’s only one other time when this happened: Grover Cleveland, like Trump, also from New York, was elected in 1884, lost a re-election bid in 1888, and then won again in 1892.) I am among the many people—who may well number in the hundreds of millions of Americans—who are surprised by this outcome, even more so than by Trump’s initial election to the presidency in 2016.

I will probably have more to say about President Trump at some point, perhaps in response to something significant that happens on his watch. But as I contemplate his inauguration in 2025 from your imagined perspective as an adult, my guess is that he will seem irrelevant—not someone beloved or hated, as he is right now, but rather trivial. You will recognize the name as the person who was the leader of the United States of America in the year in which you drew your first breath. Odds are you will be able to name a fact or phrase or two associated with him. (Something about a wall.) Perhaps you will have had a history class in which his name comes up, and for which you answered a question or two on an exam that you have long since forgotten. Even if there are conditions in your life that are the result of things that happened during the Trump administration, this is unlikely to be something about which you know or care very much because there will be other things—current controversies, other realities—that will seem far more pressing.

This is kind of what happened with Grover Cleveland. Unlike Trump, he came into the White House as a good government reformer, someone who was willing to buck his own Democratic party in his relative conservatism on fiscal matters. (He was a so-called Gold Bug. Once upon a time, virtually everyone who followed the news would have known what that meant; now virtually no one does.) Cleveland’s second term was difficult because it coincided with the worst economic downturn in U.S. history until the Great Depression, and he was pushed aside by his own party in favor of William Jennings Bryan (a legend!) who lost to Republican William McKinley. McKinley was popular but assassinated, replaced by the far more charismatic Theodore Roosevelt, who is probably still vomiting in his grave to think that Trump, a rich arriviste with no sense of noblesse oblige, ever became president in the first place. Anyway, Cleveland was considered an important figure for the next half-century, regarded as among the most significant presidents the U.S. has had. Now he’s a footnote.

The person who was president when I drew my first breath was John F. Kennedy. He was an exciting figure because he was young and urbane with a beautiful wife and young children. He was also the first Catholic to be elected president, which was once a significant cultural barrier to overcome. (Ever since, it seems every candidate has to make some claim of being the first member of some marginalized group; the cross Trump carries is that of an outer-borough wanna-be who was never considered a member of the cool plutocratic crowd.) Even your great-grandfather Jim, a lifelong Republican, cast his ballot for Kennedy because he was Catholic. Personally, I have long regarded Kennedy as among the most overrated presidents, a man of style more than substance with little real power in operating the levers of government, notwithstanding a moment of success in the Cuban Missile Crisis. (You know that one? The moment when the world almost ended?)

I consider the most consequential president of my lifetime to be Ronald Reagan. In part, that’s for parochial reasons: his two terms coincided with my late adolescence and early adulthood, always a formative period when it comes to these things. As part of my job, I explain to teenagers, all of whom have heard of Reagan but not much else, what happened on his watch. (He really defined the parameters of American politics—how close or far away you should be from him—until Trump came along.) Actually, that’s my job writ large: to try and and bring the dead back to life, however hazily or temporarily.

But not today. Today is a day when I step back and remember that the things that matter to me—like the fact that Donald Trump’s supporters, with his blessing, led an insurrection on the U.S. capitol after he lost the election of 2020, an act which I will always regard as unforgivable—are not likely to matter to you. I have no idea what you will care about. But insofar as I’m capable of caring about anything, it will be you.