Joe Biden, Donald Trump, and the vast majority of the political class in the United States are united in their belief on one of the great issues of our time: the national debt. That unity takes the form of ignoring it. Republicans, who used to say they cared, have dropped the pretense: the words “debt” and “deficit” go unmentioned in the GOP platform to be ratified this week. In the next two years, interest payments on the national debt will exceed what the government spends on Medicare. Folks: this is getting serious.

Immigration, inflation, culture wars, foreign policy: in one way or another, sooner or later, they all come down to money. The U.S. government has been spending more than it takes in, year after year, decade after decade—and it’s gotten much, much worse lately under both Trump and Biden. You simply cannot do that indefinitely. Sooner or later, and always unpredictably, it brings armies and neonatal units to a halt. Debt like this wrecked the Roman Empire. It brought about the French Revolution. It will end us. It is, truly, one of the few iron laws of history.

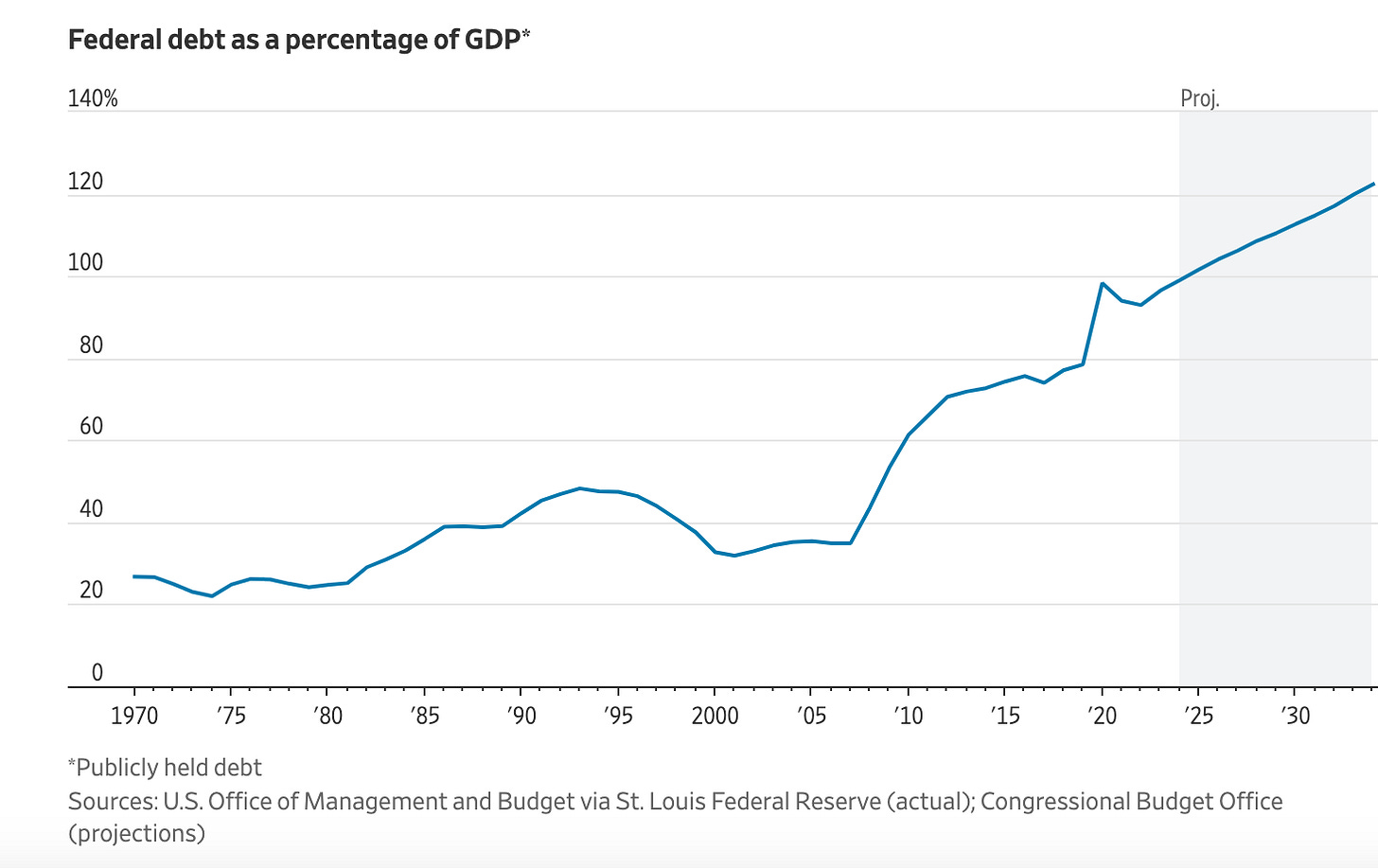

Government budgets are not household budgets. And debt can often be a good thing, whether as another name for investment or as an instrument of good fiscal management. The United States is about to reach a debt limit that matches its annual gross domestic product—a threshold it last crossed in 1946. But that was in the aftermath of the Great Depression and World War II. The nation hasn’t experienced anything resembling the scale of such crises, and there’s no end to the red ink in sight. Deficit spending made sense during Covid—but the lack of effort to account for it properly is one of the reasons why we experienced such sharp inflation (which, painful as it’s been, is nothing compared to what people in places like Greece and Argentina have experienced in recent decades, and which we may yet know).

There’s no indication that our politicians plan to do anything about the problem. Democrats love spending. Republicans love tax cuts. In the last half-century we’ve had both—often at the same time—and have dealt with the resulting budget deficits by borrowing money. Which the government could get away with, as long as interest rates were low, foreign governments (notably China) were willing to lend, and the dollar remained a global currency. All three conditions are now in question. Now we have to face the worst of both worlds: raising taxes and cutting spending. That brings mobs into the streets. Not doing it brings foreign troops into the capital.

There have been times in recent memory when government debt was an issue and successful steps were taken to combat it. When Ross Perot ran for president in 1992, many of us (myself included) considered him a kook. But he had a useful monomania about the national debt, and, as in the past, the American political system responded to a powerful third-party challenge by incorporating the message of the insurgency. In this case it was Bill Clinton who did so, pushing through painful tax increases at the start of his presidency and finishing it with a net annual surplus. Even better, the overall government debt began to decline. When George W. Bush came into office, he couldn’t resist scratching the Republican itch for tax cuts—households got sent checks for $300; big business got much more—and starting some ruinously expensive wars. There’s never been a serious attempt to restore fiscal discipline since.

We need it desperately. Sooner or later the pressure will become unavoidable—the Social Security trust fund is going to run out of money sometime in the next decade, and hell hath no electoral fury like senior citizen voters. The real danger, though, will come from the unpredictable contingencies of history: a war here; a bank run there; another pandemic. Our fiscal pants are down. If we’re not careful, we’re going to end up dangerously, and painfully, exposed.

I have an idea. Let’s cancel student debt so teachers, plumbers, farmers, truckers can help finance the education of future lawyers, doctors, bankers.