Back in 1896, when Adolph Ochs bought the New York Times, it was not a particularly distinguished newspaper. The Times had been around since 1851, when it was founded as a fairly typical mid-century paper that got on the bandwagon of the emerging Republican party. Ochs, a Tennessee Jew discreetly crashing a Gotham party, sought to put the struggling Times at the front of the journalistic pack. And his plan for doing so was encapsulated by the slogan he adopted in 1897 and which has been in the top right-hand corner of the paper ever since: “All the News That’s Fit to Print.” (In a cheeky bit of subversion, Rolling Stone adopted “All the News that Fits” as its slogan when Jann Wenner founded it in 1967.) Och’s son-in-law, Arthur Hays Sulzberger, continued the tradition in what remains a family business to this day.

“Fit,” of course, is the heart of the matter. It implies a sense of discrimination: an active effort to curate, and, yes, limit what was deemed appropriate for public discourse. An active sense of editorial judgment exercised on behalf of an audience of discerning readers.

This was something new. For the preceding century, American journalism was a freewheeling industry of fierce partisanship and gleeful exaggeration. Alexander Hamilton was at the forefront of changing largely a matter of genteel business information—the shipping news, as it was called—in founding the New York Post in 1801 as a vehicle for taking down his hated rival, Thomas Jefferson. The emerging spirit of the time was captured by an allied Federalist organ that warned: “Should the infidel Jefferson be elected to the presidency, the seal of death is that moment set on our holy religion, our churches will be prostrated, and some famous prostitute, under the title Goddess of Reason will preside in sanctuaries most high.” Jefferson, for his part, sought to sink the Hamiltonian Federalists “into an abyss from which there will be no resurrection.”

However, this new partisan press did not really take off until an explosion of cost-effective publishing technology and widespread literacy created the penny press that exploded in the 1830s. Papers such as The Baltimore Sun and New York Herald created a vast new mass culture that included not only news, but also breathless accounts of scandal, sensational phenomena (some of them hoaxes), and other forms of low-brow entertainment. Politically speaking, the master of this media was Andrew Jackson (or, more accurately political advisers such as Martin Van Buren, who also edited a newspaper at one point), who used invective, pandering, and image-making to build a political majority that lasted until the Civil War

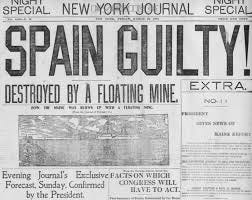

This phase of media history culminated at the end of the nineteenth century, when media moguls like William Randolph Hearst, master of “yellow journalism,” successfully whipped up enough hysteria to prod the United States in the Spanish-American War in 1898. This was an enterprise helped by papers that included photographs, comics, and other forms of entertainment that could last an entire afternoon upon the delivery of a fat Sunday paper.

Ochs was after something different. He wanted the Times to be the standard-bearer of respectability—responsible news delivered soberly and authoritatively. In this regard, he was riding the wave of the Progressive movement, which placed a new emphasis on expertise, professionalism, and objectivity. Though the old model persisted—adapted into a new tabloid form useful for reading on a subway train—the Ochs formulation gradually gained traction as the governing approach to American journalism, one that carried over into the new media of radio and television. It reached its apogee in the form of CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite: “Mr. Credibility.”

Those days, as we know, are over. The progressive journalistic order that held sway for most of the twentieth century—and which depended on curated content moderated by a fixed number of media channels—has given way to a radically decentralized system. Posting has replaced broadcasting; virality is the new index of health. Social media is smothering what may soon be a marginal “mainstream” media. Opinion is replacing reporting.

This is all a familiar story and I don’t want to belabor it. My real point is that this brave new world is really a brave old world: we’ve been here before. In the large scheme of things “all the news that’s fit to print” has been the exception, not the rule. People once had to make sense of what was going on without truly reliable sources. We will again. The question will rest on the skills we cultivate and the values we hold. It won’t be easy. But it never was.