It’s been a while since I’ve posted one of my “Sestercenntenial Moments” marking the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution and its memory in our national life. That’s because the push toward a break with Britain essentially went on hold from the fall of 1774 until the spring of 1775. But with the momentum of that saga picking up, I plan to continue the series. For more on its background, see here.

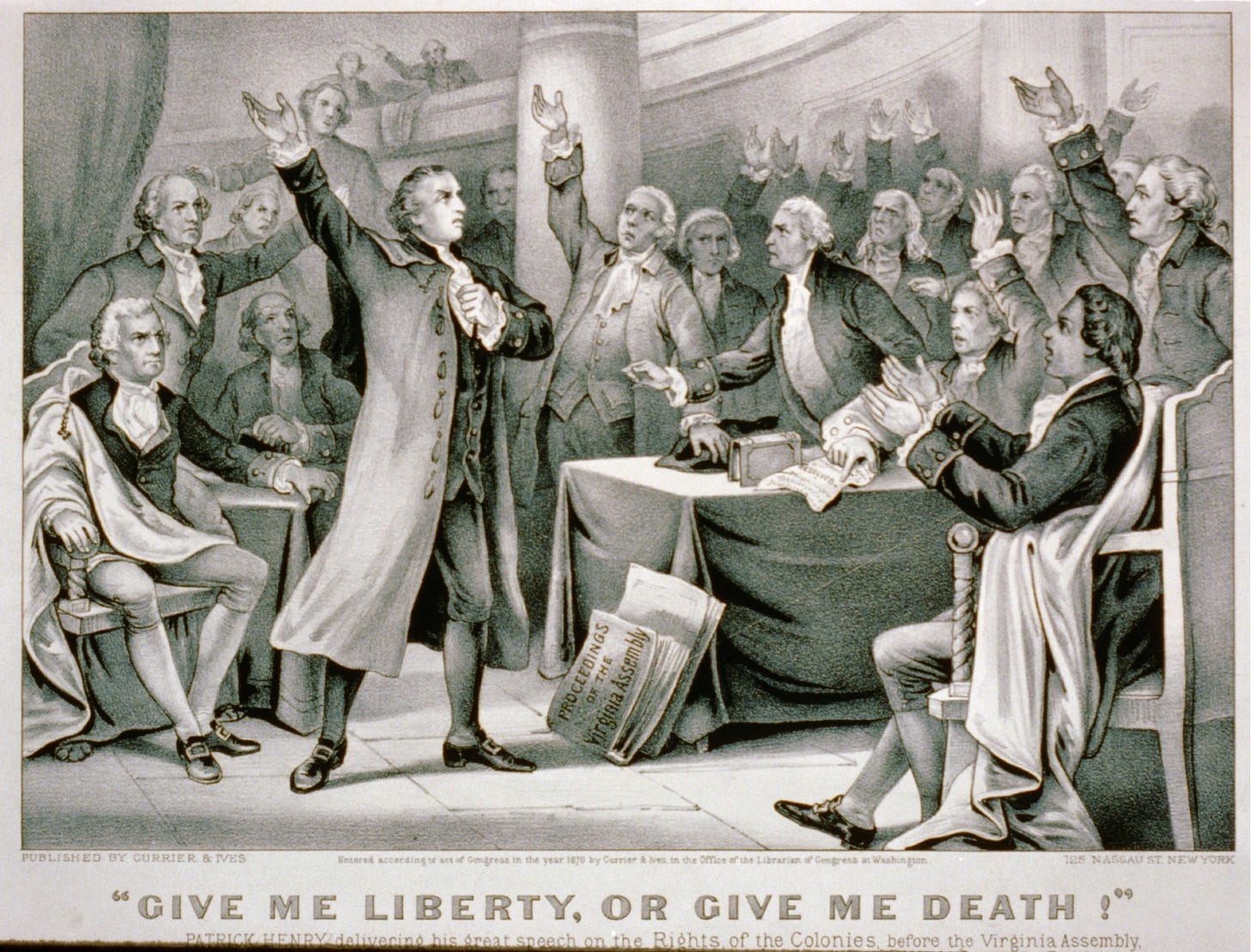

“Give me liberty or give me death!”

If Patrick Henry was a pop star, this line, which debuted on March 23, 1775, would be his signature song—the hit everybody knows, even little kids (it has, after all, found its way into generations of U.S. history textbooks). My own opinion of Henry has long been a little mixed. But reading the speech that culminates in this line—and reading it now, in a moment when the legitimacy of the efficacy of our government is actively in question—gives me a new appreciation of him.

Henry is undoubtedly a Founding Father, but not quite in the pantheon of its greatest heroes: Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, Adams. He wasn’t quite entirely reputable in his day, either. Henry was the son of a Scottish immigrant (though his mother was from good Virginia stock) and he hailed from Hanover County—one of the outer boroughs, as it were. (It was near Richmond, soon to be Virginia’s capital.) He married reasonably well, but his wife died young, leaving him with six children, and the house he was given by his father-in-law burned down. Henry ended up running a tavern his wife’s father owned, which is where Thomas Jefferson met him. While there, Henry taught himself law and then went into politics. He found his way into the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he arrived in 1765 in time to speak out against the Stamp Act, the first major step in Great Britain’s efforts to tax the colonies for the cost of the Seven Years War. “If this be treason,” he famously said at the time, “make the most of it.”

Henry was a champion of the Virginia backcountry, and this populistic streak meant, among other things, that he was at the vanguard of the effort to disestablish the Anglican Church in Virginia, which all taxpayers had to support. His allies saw him as a man of the people; his skeptics saw him as a blowhard. Henry was a guilt-ridden enslaver who spoke out against the institution even as he remained enmeshed in the tobacco economy. While figures like Adams and Jefferson moved slowly to build consensus for a break with Britain, Henry positioned himself at the radical edge. By early 1775, rage at Britain was cresting amid military action that now seemed inevitable, and Henry, who was active in the (somewhat volatile) Virginia militia, spoke at a state convention:

They tell us, sir, that we are weak; unable to cope with so formidable an adversary. But when shall we be stronger? Will it be the next week, or the next year? Will it be when we are totally disarmed, and when a British guard shall be stationed in every house? Shall we gather strength by irresolution and inaction? Shall we acquire the means of effectual resistance by lying supinely on our backs and hugging the delusive phantom of hope, until our enemies shall have bound us hand and foot? Sir, we are not weak if we make a proper use of those means which the God of nature hath placed in our power. The millions of people, armed in the holy cause of liberty, and in such a country as that which we possess, are invincible by any force which our enemy can send against us. Besides, sir, we shall not fight our battles alone. There is a just God who presides over the destinies of nations, and who will raise up friends to fight our battles for us. The battle, sir, is not to the strong alone; it is to the vigilant, the active, the brave.

“Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?” Henry concluded. “Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!” As he concluded, Henry pointed an ivory paper cutter at his chest, alluding to the Roman patriot Cato the Younger.

Reading that speech now, what strikes me is its clarity—not simply Henry’s passionate confidence, but the force and directness of his language, similar in kind and spirit to that Thomas Paine would deploy the following year in his famous galvanizing pamphlet Common Sense. The radicalism of our day, by contrast, seems cluttered, opaque, even elitist—systemic, hegemonic, structural—clouded by abstraction. There’s always a risk that the simple can become simplistic. But there’s no substitute for plain-spoken lucidity. Here I’m reminded of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s observation in his 1841 essay “Language” that “wise men pierce this rotten diction and fasten words again to visible things.” This is what we so desperately need right now to slice through the onslaught of obfuscation that pollutes our political discourse.

In the years that followed that speech, Henry remained an important figure in state and local politics, serving three terms as governor in the Revolution. After the war, he became a leading antifederalist arguing against the U.S. Constitution, fearing it ceded too much power to the federal government—a position which, however misguided, was consistent with his libertarian sensibility. Despite some strain over this, Henry maintained good relations with Washington, who was grateful to Henry for standing by him amid the crisis of the Conway Cabal, when Washington’s legitimacy was questioned during the Revolution’s dark days of late 1776 and early 1777. The president offered him a seat on the Supreme Court, which Henry turned down. He died in 1799, a few months before Washington. Henry was not first in war, first in peace, or first in the heart of his country. But he is justly honored nonetheless, and remains a relevant precedent for those seeking succor and strategies in the face of rising tyranny.