“I want to see Richmond.”

On April 3, 1865, the Union army of the Potomac, having broken the siege of Petersburg that had run for 292 days, finally entered the capital of the Confederate States of America. On April 4—160 years ago today—Lincoln and his son Tad, who turned twelve years old that day, took a ship down the James River to visit the city that had eluded his grasp for four long, bloody years.

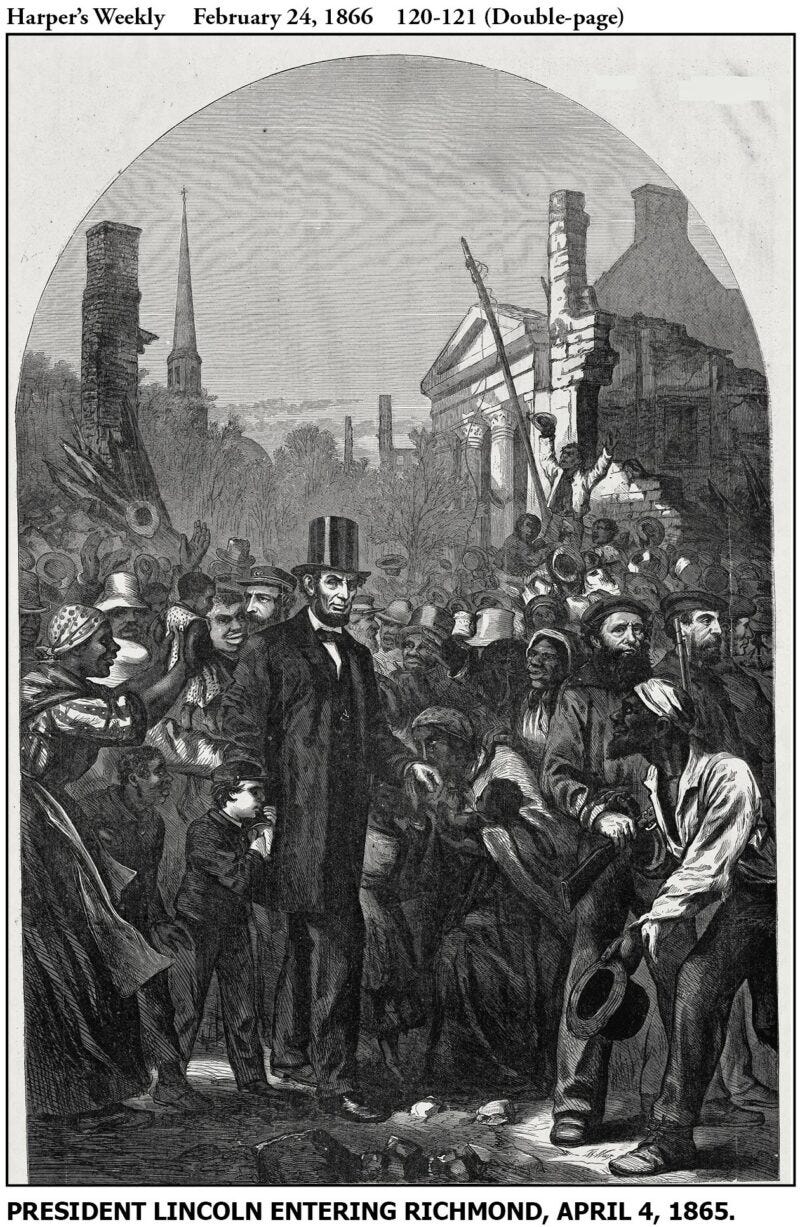

Lincoln arrived quietly, unannounced. The first people to see him was a group of African American workmen. Their leader, about sixty, dropped the spade he was using and ran to him, saying, “Bless the Lord, there is a great Messiah!” He and the others fell on their knees. Lincoln was embarrassed. “Don’t kneel to me,” he replied. “This is not right. You must kneel to God only, and thank him for the liberty you will hereafter enjoy.” A collective shout rose from the growing crowd: “Bless the Lord, Father Abrahams Come.”

Lincoln and his small party walked up Main Street. It was a warm, sunny day, and the president shed his coat, though he kept on his stovepipe hat, which made him sweat. He sought direction to the headquarters of the Union general occupying the city, which was based at what had been the Confederate White House. Lincoln’s entourage had lunch there. He couldn’t resist the opportunity to sit in the swivel chair of President Jefferson Davis, his great adversary who opposed him a mere 100 miles distance from the other White House. (Davis was at that point a fugitive; Lincoln hoped he would escape to Latin America, but he was ultimately caught and jailed.)

Lincoln proceeded to the Virginia statehouse, former home of the Confederate Congress. The hall had been hastily abandoned and probably looted—tables and chairs had been overturned, and there were documents and (worthless) Confederate bonds all over the floor. Lincoln met John A. Campbell, one of the few high-ranking Confederates remaining in the city. Lincoln wanted Campbell to gather the few remaining officials in Richmond and convene in order to formally take Virginia out of the Confederacy, promising to act with leniency. He was hoping to forestall the harsher approach sought by his friend but political opponent Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, who was pushing for more radical measures in reconstructing the Union. But Lincoln did not commit to anything, explaining that needed more time to work out the details. As he later told General Ulysses S. Grant, who would pin General Robert E. Lee’s disintegrating army at Appomattox Court House a few days later, the Confederate government was going to collapse without such formal steps.

Next Lincoln toured Richmond’s neighborhoods. In affluent parts of the city, shades were drawn, and no one was to be seen; in working-class districts, he was surrounded by enthusiastic crowds. The president’s security detail was deeply concerned for his safety. Lincoln was not. “I cannot bring myself to believe that any human being lives who would do me harm,” he said.

Lincoln arrived back in Washington on April 8. On the trip back, he regaled his traveling party with excerpts from one of his favorite plays, Macbeth. He recited a passage where the titular character, having achieved his murderous aims, reflects on the king he has killed:

…Duncan is in his grave:

After life’s fitful fever he sleeps well,

Treason has done his worst; nor steel, nor poison,

Malice domestic, foreign levy, nothing

Can touch him further

A week later Lincoln himself would be dead. Aides preparing his body for burial found a $5 Confederate bill in his pocket.