Rock from the Sticks

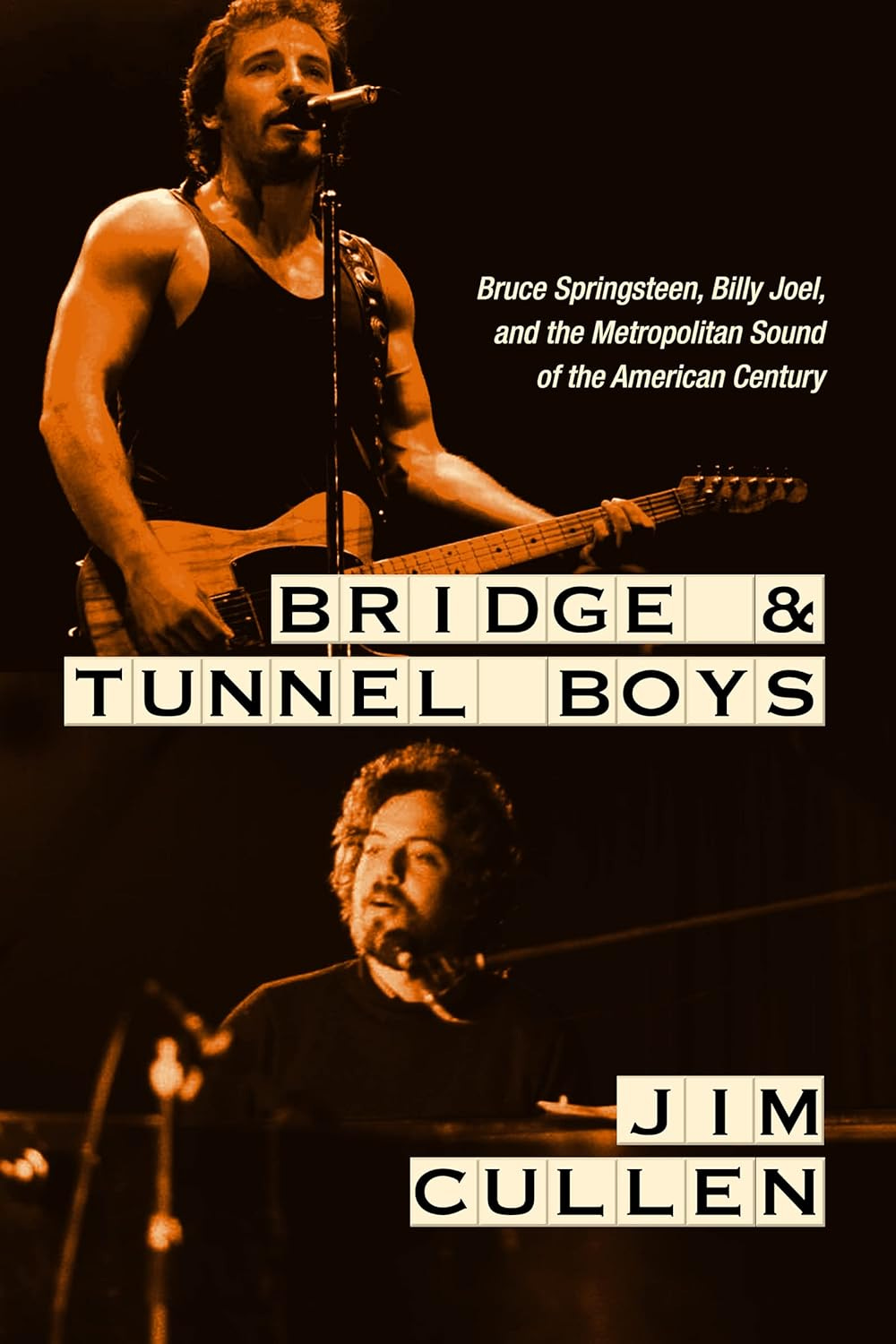

An excerpt of my new book "Bridge & Tunnel Boys"—Now available!

“There’s a little bit of an inferiority complex, which I find charming.”

—Billy Joel on Long Island life, 2010

“We, who bear the coolness of the forever uncool.”

—Bruce Springsteen, New Jersey Hall of Fame induction speech, 2008.

Our story begins in December of 1977, at architect, designer, and man-about-town Sam LeTulle's party for Harriet de Rosiere, a vivacious American woman married to a French vicomte. The party was crowded—about eighty people that included a couple of Vanderbilts and Manhattan doyenne Nan Kempner, entertained by an ensemble of Brazilian musicians performing a bossa nova—but the host had difficulty limiting the guest list. “All of New York is here,” exulted one participant.

“There are too many people I love,”LeTulle explained as he moved between the reception rooms, the foyer, the staircases and the nooks and crannies of his three‐story townhouse. “I never know when to say no.”

A New York Times reporter at the scene explained that this was not a problem for one of the guests, Steve Rubell, co-owner of the famously exclusive Studio 54 nightclub in Manhattan. Indeed, Elizabeth Fondaras, a pillar of the city's conservative social scene, confessed she had never gone to Studio 54, for fear of being turned away. “On the weekends, we get all the bridge and tunnel people who try to get in,” Rubell explained by way of the club’s stringent admission gauntlet. Fondaras didn’t understand the reference, so Rubell elaborated: “The people from Queens and Staten Island and those places.” He told her that if she let him know in advance, he would make sure she got in.

Bridge and tunnel. The phrase refers to the fact that those who live on the periphery of Manhattan—which, as everyone knows, is really the heart of New York City—must cross bodies of water by ferry, rail, or car to reach the island, though its connotations extend more widely. It’s not a nice term. But it’s a highly elastic one in which the disdain stretches in more than one direction. These days, one often hears it in the context of Broadway culture—theater insiders who lament the bland tastes of suburbanites who flock to dismayingly middlebrow musicals instead of more challenging fare, predilections all the more galling because the city’s theatrical culture depends on the economic infusions those suburbanites provide. But the condescension takes on other forms as well. The bridge and tunnel crowd is not simply lacking in taste or wealth; it also evinces a host of other vices for which contempt, veiled or not, is understood to be justified. Environmental despoliation. Selfish fiscal libertarianism. And, of course, racism.

Like most stereotypes, these perceptions are not without foundation. For the last century, urban and suburban sprawl has contributed to climate change. Those on the urban periphery often do take a skeptical, if not hostile, stance toward government programs in which they are not direct beneficiaries. White flight really is one of the major demographic facts of American life since World War II, a form of racial segregation, which, unlike that of the pre-1960s South, has been all the more insidious for its successful resistance to legal and political challenges. Those who inhabit these spaces can perhaps be legitimately charged with a form of bad faith: extracting the best of what the city has to offer while distancing themselves, literally and figuratively, from that which they don’t like.

Of course, the picture is a little more complicated than that. Many of the people who inhabit Greater New York—a term that encompasses the four outer boroughs of the city (Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx and Staten Island) and the surrounding counties of the tri-state area (New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut)—simply can’t afford to live in Manhattan. A host of factors ranging from tax incentives to educational opportunities lure them to the periphery. And while racial segregation remains an important reality, these habitats—sometimes urban themselves, as well as suburban and even rural, with economies that are mixed and promote traffic in multiple directions—have substantially diversified in recent decades, achieving varying degrees of racial diversity even as they segregate in other ways at the same time. It also must be noted that the faults of these metropolitans are hardly theirs alone. Those who point fingers are often doing little more than virtue-signaling from perches of privilege.

The people we’re talking about here are what might be termed a middling sort—generally not impoverished, but generally not wealthy, either. The term “middle class” may be one of the most elusive and even evasive in the English language, but it serves a purpose in capturing a reality, however broad, imprecise, or diffuse. There’s an accompanying reality as well: that within this middling sort that has long been an element—maddeningly hard to pin down—of socioeconomic mobility (in more than one direction). It has waxed and waned. And it has been at the center, whether as a matter of expectation or experience, of what it has meant to be an American.

This book explores the careers of two figures with strikingly parallel experiences who embodied this metropolitan experience in the second half of the twentieth century. They too were of a middling sort: people of modest backgrounds from the urban periphery who came of age at a time of unusual mobility and who experienced more mobility than most. That they could do so reflected a trend of road historical trends of relative national affluence whose roots dated back centuries. But it was also a matter of a highly unusual moment, one whose likes had never really happened before and are unlikely to happen again, of unusual hope and promise. We should understand that at the outset.

Order your copy of Bridge & Tunnel Boys!