Springsteen Envy

Some notes on a disreputable emotion

Within the general ambit of, well, Americana, I try to cover a lot of ground in this newsletter. But of course there are all kinds of things that I don’t write about. Some of this is a matter of ignorance: there are many subjects I don’t know at all, and others that I know enough to know that I don’t have anything of value to add. Some of it is a matter of discretion: I try to avoid topics I believe will get me or others in trouble, which can at times be challenging because I operate without much in the way of an editor other than Grammarly to buff my prose—and because finding topics that are both safe and interesting can be a tough proposition. Finally, some of it is a matter of vanity: I don’t like to express ideas that will reflect badly on me. Yet I also place a pretty high value on honesty, in large measure because while truth is not always beautiful, it can often be useful to oneself and others.

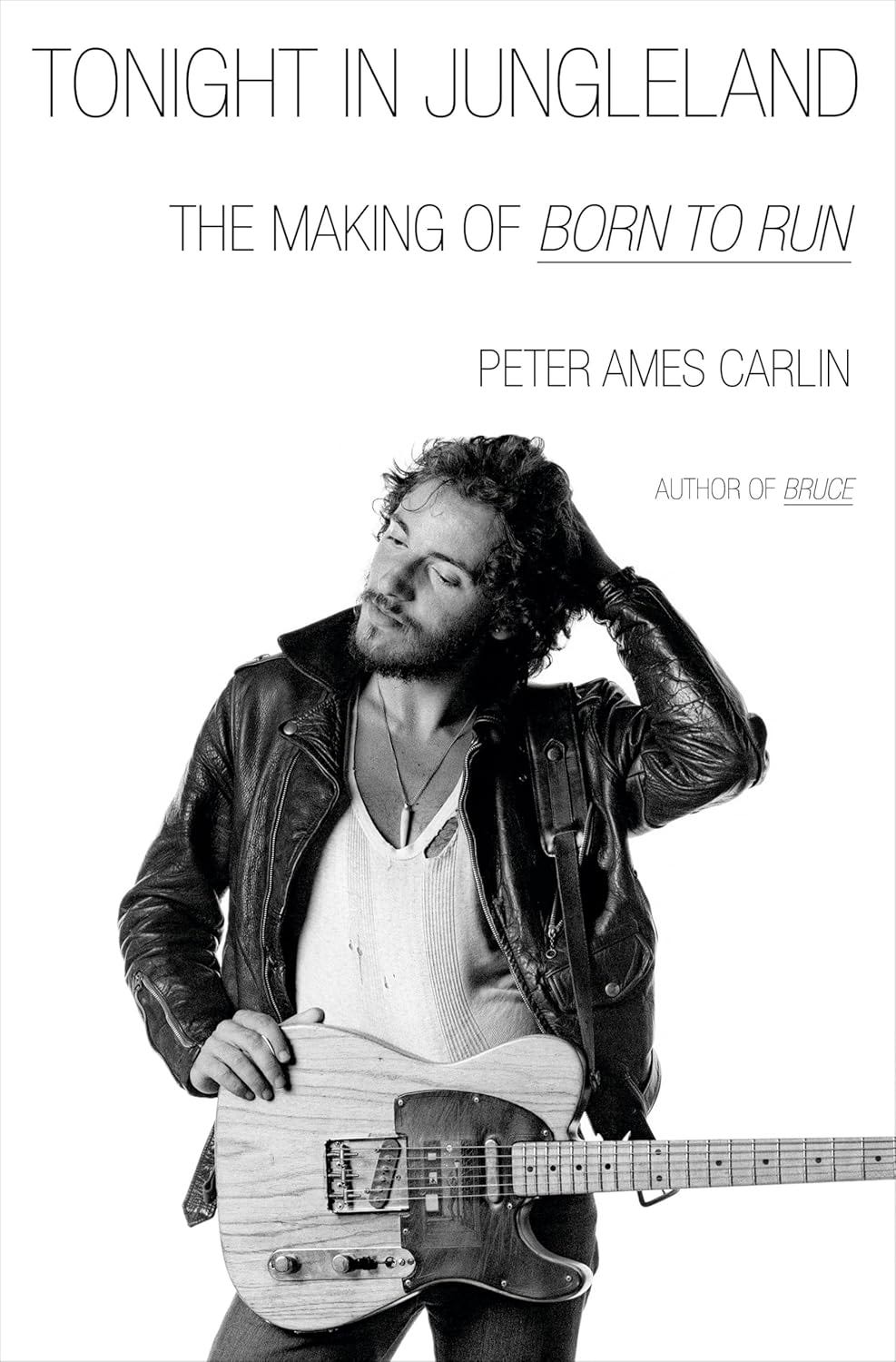

That’s why I want to write today about the powerful human experience of envy. And to do so in the context of my friend Peter Ames Carlin’s new book Tonight in Jungleland: The Making of Born to Run (which, as I write, occupies a perch on the New York Times Bestseller List).

Let me start with another preliminary piece of candor: This is not a book I particularly wanted to read. In part, this is because the making of Born to Run is a subject I know well, having written about it in two Springsteen books of my own. One of them, Born in the USA: Bruce Springsteen in American Life, was reissued in a third edition earlier this year, and having finished a fairly substantial revision of that project, I was, to use a term Springsteen himself once used to describe his exhaustion with his own fame, “Bruced out.” The other book, Bridge & Tunnel Boys, compared Springsteen’s career with that of Billy Joel, subject of a rapturously reviewed recent documentary that I haven’t been particularly interested in watching, either. But still feeling a twinge of personal obligation to stay current in my field, and grateful to Carlin for arranging to have the book sent to me, I took it along on a recent vacation, reading most of it on a plane.

Tonight in Jungleland is a good book. Beyond the not inconsiderable fact of a story, however familiar, well told, there are two things that distinguish it. The first is that Carlin does a fine job of tracing how Springsteen’s signature song evolved, usefully sampling drafts of lyrics that got steadily better in the revision process and illuminating Springsteen’s painstaking commitment to craft (a commitment, paradoxically, that feels spontaneous in many of his records and especially his meticulously planned live shows). The other is that Carlin elegantly threads a late-night conversation Springsteen had on his 75th birthday last year throughout the book to give his narrative a sense of freshness and updated reflection. Carlin, who has written books about the Beach Boys, Paul McCartney, and Paul Simon, among others, is a real pro, and it is always a pleasure to find oneself in the hands of someone who knows what he’s doing.

You can probably sense where I’m going with the envy theme here, but before getting to that, I want to pause for a moment to talk about the experience of experiencing Springsteen himself.

I’ve never met him (a topic to which I will also return). Notwithstanding this significant limitation, I have nevertheless lived with Springsteen for half a century of listening, watching, reading, and writing about him. I have also met with many people who have met him, and have picked up a lot that way. To say that I have long found him fascinating is an understatement. He ranks with Abraham Lincoln as a person from whom I extrapolate advice on how to live.

But Bruce Springsteen can be exhausting. I mean that in a number of fairly trivial ways, among them fatigue with the crafty care with which he has managed his image, artistic wells he has run dry, and the seemingly unending stream of trivia on set lists, concert tours, alternative takes, and what has now become fan culture on a scale that could give a Grateful Dead fan pause. I am not among those who have acquired his latest release Tracks II: The Lost Albums, a $300 proposition.

But what really exhausts me about Springsteen is the way dual indispensable sources of his success—Promethean talent coupled with tireless commitment—reveal my limits and thus tap a wearisome sense of envy. I have never wanted to be a rock star. And I have never imagined I would ever become rich or famous on the scale he has. But I always related to him as a fellow writer (him songs; me books) involved in a comparable lifelong quest in the arts. I have never enjoyed success anywhere remotely near where he has, however. That’s because I’m a lot less talented than he is.

This isn’t the whole story (insofar as it’s possible to tell the whole story about anything). What set Springsteen apart was not simply that he was a genius. It’s the depth of his commitment to his art, and the risks he was willing to take to realize it—a big part of the story Carlin tells in Tonight in Jungleland. By the time Springsteen was in high school, he had already decided it was rock & roll or bust. And there were lots of busts along the way. When you read back over what has now become a voluminous literature, many people from many walks of life recognized instantly that Springsteen was something special. But to use Joni Mitchell’s apt phrase, the star-making machinery is complex, and many would-be stars got mangled by it, as he almost did when he signed a contract on the hood of a car in a dark parking lot. Springsteen’s back was truly against the wall when he was making Born to Run in 1974-75. After years of hard work, he achieved “instant” success by getting signed to Columbia Records, but his first two records stiffed, and the label was turning its attention to another recent signing: Billy Joel (who had his own struggles). There was talk of dropping Springsteen, and impatient Columbia executives only advanced him enough money to make a single song that would decide his fate. That song was, of course, “Born to Run.” Springsteen drove everyone around him nuts with his perfectionism in making the album that followed. The rest, we’ll say in the interests of brevity, is history.

Which brings us back to Peter Ames Carlin. Back in 2011, I met Carlin at a Springsteen conference at Monmouth University, where he was working on what would become his bestselling 2012 biography Bruce. The genial Seattle native offered to give me a personal tour of Springsteen’s hometown of Freehold, New Jersey, a kindness I eagerly accepted, and I have used the mental map he provided me on subsequent trips there.

After our tour that day, Carlin and I repaired to Federici’s, a favorite Springsteen pizza haunt. Over beers at the bar, Carlin told me the story of how he wrote the book. Initially, he explained, no one in Springsteen’s camp would talk with him. He knew this would be the case; Springsteen’s semi-official biographer, the famed rock critic Dave Marsh, is married to Springsteen manager Barbara Carr, and Team Springsteen is small, tight, and loyal. But Carlin persisted, nibbling at the edges and gradually moving up the food chain to the point where Springsteen decided it would be better to cooperate than resist—perhaps he recognized a kindred spirit of persistence. As a result, Carlin enjoyed unique access to the Boss and his operation, and those ties made the subsequent biography, as well as Tonight in Jungleland, distinctive. Carlin, for example, was given access to the Born to Run tapes in the very studio where it was recorded.

Now you could say, accurately, that I envy Carlin’s access and the quality of the two Springsteen books he has written, though I’ve always thought we are engaged in different enterprises (I’m a scholar; he’s a journalist). What I really envy is the tenaciousness he showed and the rejection he allowed himself to experience on the way to writing these books. Among others: Paul Simon subsequently proved to be an impossible nut for Carlin to crack. (Simon is someone whom I have met, and whom I did not find to be a particularly pleasant person, when he came to a team-taught class that his son, a terrific kid, was taking on classic albums that included Graceland.) I thought I had too much pride—what I really had was too much cowardice—to be the kind of guy who hung around outside the stage door, or talk my way into an inner circle. It’s why I was a failure in my stint as a news reporter (sent out to interview illegal immigrants in the summer of 1984, for example, I lacked the gumption to get the job done). People who are willing and able to do such things have rare and valuable qualities that benefit us all. If I’d had them, I might have gone further than I did.

I don’t want to be too simplistic about this. I got far enough, in part because I was willing to experience rejection, even if not on the scale that Springsteen, Carlin, and others did. And one should never underestimate the role of luck in life outcomes. But I have also come to understand that there are some solid reasons why I occupy my station in life, reasons that are a matter of real skills and diligence on my part, and reasons that reflect real shortcomings and a temperament that, like all temperaments, has its advantages and disadvantages. I take some comfort in this: my fate has not been random, and recognizing what I’ve failed to do helps me appreciate what I did accomplish. And to appreciate what others did, and to take real pleasure in experiencing them for who they are. (Along with occasional envy.)

But I don’t want that to be the moral of the story in this particular post. Instead, what I’m hoping—amid uncertainty and anxiety—is that, here, in my seventh decade, I still might be able to actually learn something. To be a little more tenacious, to accept a little more rejection, in trying to move beyond safe projects and reliable returns. I don’t know if I can do it. But it’s about time.

Self examination takes a lot of courage!

👍