I was asked to provide a brief reaction to the election for Current magazine, which ran this morning. In it, I continued in a Jacksonian vein I explored in a piece I wrote that ran in the Washington Post in 2016 after Donald Trump was elected the first time. In this one, I talk about the parallels in realizing that Trumpism, like Jacksonianism, was actually a long-term movement. Because the piece is brief, I think I can quote it in its entirety:

Two hundred years ago, respectable Americans across a wide range of views were deeply relieved by the outcome of the presidential election of 1824, in which John Quincy Adams defeated Andrew Jackson for the presidency. (Jackson won pluralities of the popular vote and Electoral College; Adams prevailed when Congressman Henry Clay threw his support to him and was then named Secretary of State, a deal dubbed a “corrupt bargain” by Jackson supporters.) The surviving Founding Fathers considered Jackson, whose dubious conduct included a freelance invasion of Florida, a dictator in the making. Thomas Jefferson called him “one of the most unfit men I know for such a place. He has very little respect for law.”

Four years later Jackson won the White House in a landslide. And four years after that, he won vindication (again) in re-election, defeating Henry Clay. (And four years after that, his hand-picked successor, Martin Van Buren continued the streak.) Jackson’s impact on American politics was profound; it was on his watch that words like “party” and “democracy” ceased to be four-letter words. The Founders, after all, had all been republicans—lower case, of course.

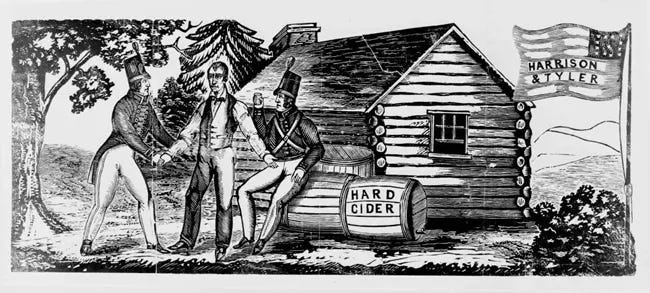

By 1840, opposition to Jackson, which gathered around Henry Clay to form the Whig party, decided that if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em: They nominated William Henry Harrison for president in the so-called “Hard Cider and Log Cabin” campaign. The notion of Harrison, a member of the Virginia planter aristocracy, as a man of the people was ridiculous. But the messaging worked: Harrison was elected. And then he died a month later. His successor John Tyler—“His Accidency”—essentially returned to business as usual. It took another generation for the Whigs to generate a more authentic log cabin politician—one with a towering intellect to match his political skills—who would ascend to the presidency.

It’s time to break out the hard cider, Democrats.

I’ll note one key difference between now and then: the 21st-century working class is now majority female. I believe that the right woman can win.