What can I do?

You might say it’s the critical existential question of our lifetimes. In childhood, it’s a matter of what we’re permitted, given the limits imposed by the adults responsible for our welfare. In adolescence, it’s one of surveying a series of available choices, like a college major or an occupational path. For adults, the question is often rhetorical—I mean, sure, I could do otherwise, but realistically, what choice do I really have given the choices I’ve made and the burdens I carry? In old age, where fading faculties diminish remaining prospects, the query takes on a poignant dimension as one seeks to identify the remaining possibilities for productive activity.

Seventy-three-year-old Bruce Springsteen has enjoyed a decade of remarkable productivity. In 2012, he released Wrecking Ball, an ambitious album of militant class conflict in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis that he considered a major statement. He followed it in 2014 with High Hopes, which also went to number one. In 2016 Springsteen published his bestselling memoir, Born to Run. (The coffee-table book based on his podcast conversations with former president Barack Obama, Renegades, was also a bestseller in 2021.) In 2017, he made his debut on the Great White Way with Springsteen on Broadway. In 2019, he released Western Stars, a suite of songs modeled on the music of Southern California in the 1970s. And then, in 2020 he reunited with his beloved E Street Band for Letter to You, a valentine to his youth and his fans. These records were chart-toppers as well. He also went on tour in 2016-17 and plans to hit the road again for sellout shows in 2023. Phew!

And yet, amid a flurry of activity that could well be taxing to someone half his age, there were signs Springsteen’s powers were fading. Springsteen himself was disappointed with Wrecking Ball. Though Obama used the leadoff track, the anthemic “We Take Care of Our Own,” as a campaign song in his 2012 re-election campaign, the album cooled quickly. “Wrecking Ball was received with a lot less fanfare than I thought it would be,” Springsteen mused in his memoir. “I thought this was one of my most powerful records and I went out looking for it all.” None of the albums that followed had even that high a profile. Moreover, High Hopes and Letter to You were marked by what could be termed filler: cover tunes and re-recordings of songs that were already part of his catalog. (There was some good new stuff along the way; see, for example, “Hunter of Invisible Game,” with its self-aware lines “Strength is vanity and time is illusion / I feel you breathing, the rest is confusion.”) An increasingly retrospective air has characterized his work.

One cannot fairly criticize Springsteen for resting on his laurels. But it’s also impossible to ignore the fact that he’s simply not the titan he used to be, even as he commands the affection and respect of presidents and late-night television hosts, among millions of fans—relatively few of whom, however, are actively following him anymore.

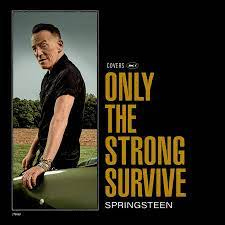

This complex context is important to consider in light of Springsteen’s latest release, Only the Strong Survive. (It has a subtitle: “Covers, Volume I,” and indeed he indicated in a recent interview in Rolling Stone that Volume II is in the works.) The hitmaking veteran recording an album of standards has a long and venerable tradition in pop music, and some rock stars, notably whiskey-tenor Rod Stewart, have gained a new lease on life with them. But they also usually speak to an implicit ebbing of creativity. Springsteen has been paying homage to his predecessors for over half a century, and a playful willingness to perform songs by younger peers has been a staple of his recent live shows. But such performances have always been in active dialogue with his own mountainous body of work. Such creative friction is what quietly drives Western Stars, an album of original songs that’s probably Springsteen’s best work of the decade (or more) and one I suspect Nashville artists will be mining for years to come. But that dialogic dynamic is not as strong on this record, a collection of mostly Motown and Soul classics.

Springsteen is not content to simply phone it in. Only the Strong Survive reflects a strong curatorial impulse that has informed his work at least since the time of Born to Run, an album he made while listening obsessively to the music of the late fifties and early sixties. What we have here is a collection of songs that range from the obscure to the unexpectedly familiar. The first single from the album, “Do I Love You? (Indeed I Do”), was first written by Jerry Butler and recorded by Frank Wilson on a Motown subsidiary label, Soul Records, in 1965. But Motown mogul Berry Gordy didn’t like what he heard, and the demos were destroyed, making the handful of remaining copies a collector’s item. (You can actually hear it for yourself here.) The next single from the album, “Nightshift,” is a loving tribute to Marvin Gaye and Jackie Wilson that was of course a major hit for the post-Lionel Richie Commodores in 1985. And so the album goes, almost forgotten gems like Butler’s 1968 hit “Hey, Western Union Man,” co-written with the dynamic Philly Sound duo Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, alternating with crowd-pleasing classics like the 1961 Supremes classic “Someday We’ll Be Together.” Almost all this music was first written and recorded by black artists; the exception is the blue-eyed soul of “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore,” first recorded by Frankie Valli in 1965 and a hit for the Walker Brothers in 1966.

Few white pop musicians today would try—or get away with—making an album that could plausibly be charged with cultural appropriation. But it’s unlikely most of those who monitor such offenses will care. Like Eric Clapton (who was also a major innovator of the blues idiom on which he built his career), or Van Morrison (who seamlessly fused African American and Celtic strains into a unique synthesis that was an important influence on the young Springsteen), he is too deeply immersed, and too reverent of his sources, to be effectively accused of glib exploitation.

That’s part of the problem. Only the Strong Survive is actually a beautiful record. The strings—in profusion here—are honeyed; the production gleams. The background vocalists, who in his live performances seem no less curated by gender and race, are impeccable. The musicians, and in particular the drummer/producer Ron Aniello, are worthy of Elvis Presley’s TCB ensembles of the seventies, which propped him up amid his descent into self-destruction. Unlike Presley, however, Springsteen remains an active and engaged student: the album is actually a means for him to work on his voice (much like his 1992 album Human Touch was a vehicle for him to work on his guitar playing—check out the title track), and he sings with more careful diction than he does on his own songs. His live and video performances feature movement and gesture that come straight out of the Diana Ross playbook. Really: it’s uncanny. But it’s also unclear what he’s adding to these songs by recording them.

Ironically, the most potent message that comes out of this record is an implicitly political one. In absorbing this music, recording it, and actively striving to keep it in circulation in his now narrower ambit, Springsteen is affirming the power of racial integration as the basis of a meaningful life. It’s not black music or white music, he seems to be saying. It’s American music. We should recognize and savor it. This is not currently a fashionable stance in an elite culture eager to protect the integrity of particularistic identities, and Springsteen himself, who has always considered himself a man of the left, has little interest in waging cultural war, especially anything that smacks of sympathy with a bigoted conservatism. He’s doing what he can to keep the faith of a once and youthful King. It’s sadly uplifting.

* * *

With thanks to Peter Ames Carlin for helping me crystallize my thinking.

Looking for a stocking stuffer? Check out my new book 1980: America’s Pivotal Year.