As we all know, we’re living in a time when the partisan political loyalties have become far more fluid than they have been in at least a half-century—“dealignment,” to use the term of pollster Frank Luntz. Once upon a time, the Democrats were the party of the working class; now they’re dominated by the college-educated. They were also the party of racial minorities, though significant proportions of such people have migrated to the Republicans. The GOP, for its part, has long been the champion of free trade, and yet now we have an administration that is aggressively pursuing tariffs. It was the staunch opponent of Russia; now it seems to be an ally. And so on.

But in all of this there has been one thing that has remained constant. Republicans have always—always—embraced tax cuts as the solution to every economic problem. When out of power, the GOP has played the role of fiscal hawk, seeking to cut federal spending in the name of balanced budgets. But when they have controlled Congress and the White House, there was never a bad time to cut taxes, budget deficits be damned. The exception—George H.W. Bush—proves the rule. After promising “Read my lips: no new taxes” in 1988, he signed tax hikes into law the following year, a broken promise that haunted him with his base. He lost re-election. His son, George W. Bush, took a government surplus and turned it into a deficit by sending Americans checks in 2001 for pennies on the corporate dollar in tax write-offs.

When Donald Trump ran for president as a Republican in 2016, it was clear that he was something new under the sun, challenging all kinds of GOP pieties in foreign policy and vowing to protect liberal sacred cows like Social Security. But even he affirmed core Republican doctrine in prioritizing tax cuts. Indeed, other than the administration’s spectacular success in developing a COVID-19 vaccine in Operation Warp Speed—which Democrats are loath to admit and which Trump studiously avoids taking credit for—the most important thing to happen on his watch during his first term was pushing through a massive tax cut bill in 2017. It’s this commitment more than any other that has Republicans sticking with him in the face of some pretty serious doubts on other fronts.

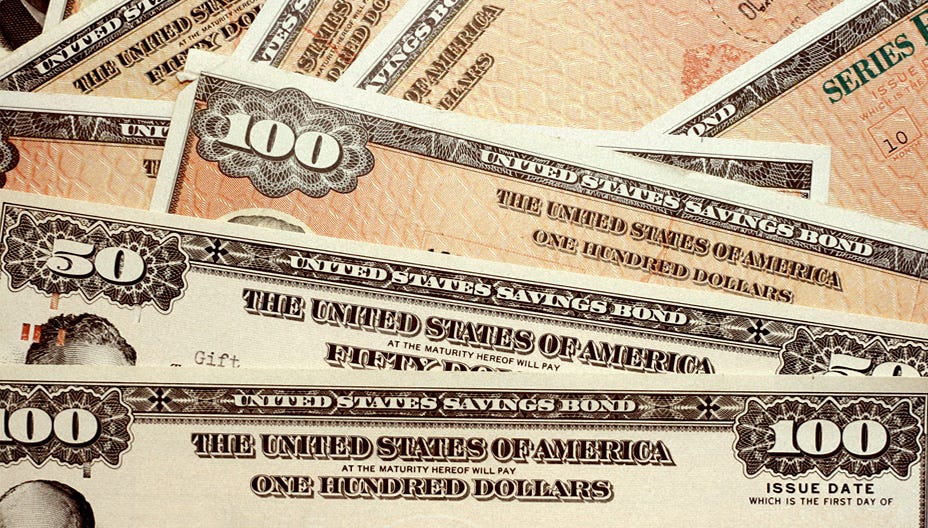

In recent decades, tax cuts have required various forms of budgetary legerdemain to obscure the chronic budget deficits the nation has run since the Reagan administration. The last time the United States balanced its annual books and actually began to chip away at its gargantuan public debt was the end of the Clinton administration. That’s because Clinton—who was very eager to behave like a traditional Democrat when it came to expanding welfare programs—violated his deepest instincts upon coming into office in 1993 by raising taxes to calm wary financial markets. This is what prompted his irate adviser James Carville to famously say that "I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody."

Even Donald Trump. Even in his second term, Donald Trump wants to behave like a traditional Republican by extending the tax cuts he rammed through in 2017. Republicans were long able to get away with this because they were always perceived by Wall Street and Main Street alike as the party of business and fiscal discipline. And many Republicans still feel this way. But there have been recent tremors that this might not be true any longer. We saw this in Trump’s recent massive imposition of tariffs. Lots of people complained, but it was only when bond traders started saying they wanted higher interest rates as the price of buying government debt that Trump backed off. Creeping rises in bond yields creeped him out. As well they should.

It appears Trump actually toyed with the idea of raising taxes on the highest earners in coming up with his new budget proposals. But party leaders convinced him to back off that means of raising revenue in favor of the usual tactics of trying to cut the federal commitment to welfare programs like food stamps and Medicaid. But this is tricky because the GOP is now a working-class party, many of whose voters in red states are deeply dependent on such support. Even now, in the choice between the businessman and the bus driver, the party’s traditional loyalty remains steadfast.

Republicans may be able to get away with stiffing their new working-class friends. But they remain in bondage to the debt markets, and to a now unprecedented degree they’re playing with fire. It may be that they will push through these tax cuts, putting lipstick on the fiscal pig in order to do so. And maybe bond traders at home and abroad will buy what they’re selling. But maybe not, and bond yields will continue their rise. Or—perhaps not likely but possible—the markets will decide to lose faith in the government to manage its finances. The results would be disastrous.

During the American Revolution, which began 250 years ago last month, the nascent U.S. government created a currency known as the Continental to pay its bills. But lacking firm financial backing, it rapidly depreciated to the point where it became proverbial to describe something as worthless by saying it was “not worth a Continental.” For the last century, by contrast, one would describe a confident outcome by saying it was “sound as a dollar.” We edge closer to an uncomfortable reckoning where the dollar’s value may be more Continental than we think.