This is an installment of “Sestercenntenial Moments,” marking the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution and its memory in our national life. For more on the background of the series, see here.

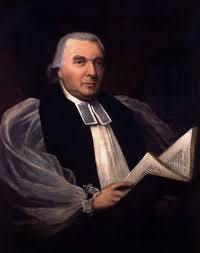

On November 15, 1774, an Anglican minister named Samuel Seabury joined what was now a furious pamphlet war in the escalating conflict between Britain and America by publishing Free Thoughts on the Proceedings of the Continental Congress under the pen name A. W. Farmer—an abbreviation for "A Westchester Farmer." As was typical at the time, Seabury adopted a pseudonym, and like Founding Father Jonathan Dickinson, famous for his 1765 tract Letters from a Pennsylvania Farmer, was masquerading as a more plebian figure than he actually was. Up until the time of Seabury's entrance into the arena, much of the discourse had been about the propriety and effectiveness, or lack thereof, of the British government's behavior. But by the fall of 1774, the situation had proceeded far beyond that: the colonists had created their own government through the First Continental Congress, and were setting a national agenda that included The Association, an agreement to boycott trade with Britain.

Seabury thought this was a terrible mistake. The opening of the pamphlet makes his case succinctly:

The American Colonies are unhappily involved in a scene of confusion and discord. The bands of civil society are broken; the authority of government weakened, and in some instances taken away: Individuals are deprived of their liberty; their property is frequently invaded by violence, and not a single Magistrate has had courage or virtue enough to interpose. From this distressed situation it was hoped, that the wisdom and prudence of the Congress lately assembled at Philadelphia, would have delivered us. The eyes of all men were turned to them. We ardently expected that some prudent scheme of accommodating our unhappy disputes with the Mother-Country, would have been adopted and pursued. But alas! they are broken up without ever attempting it: they have taken no one step that tended to peace: they have gone on from bad to worse, and have either ignorantly misunderstood, carelessly neglected, or basely betrayed the interests of all the Colonies.

In short, the Continental Congress is not a legitimate government, Seabury argued. It doesn’t speak for you! Many, of course—including Alexander Hamilton, who would soon respond to Seabury with his own pamphlet, The Farmer Refuted, which would later be immortalized in the musical Hamilton—disagreed emphatically. And that is what the American Revolution—all revolutions—are at heart: a legitimacy crisis. Who speaks for the people? That’s always the question. Sometimes it’s answered at the ballot box—though that’s not the only, even primary, way in which it gets answered when there’s a serious dispute. The lack of clarity about an answer is how wars start.

By November of 1774, the lack of consensus on the answer to this question had never been more disputed in British North America. The question of war was no longer an if. It had become a when.